In 2003 two young artists bought a house in Sydney – a headline in itself. This house, however, was to be demolished and so the various deconstructed materials were removed from the house site in an inner suburb and delivered to a large gallery space near the CBD.

Sean Cordeiro and Claire Healy then set about classifying, ordering, cutting to length and very neatly stacking the materials within a designated square on the floor. The pile – about a metre high – seemed to comprise the house materials in order from the ground up, first the stumps, then the floor boards, and so on, finally capped by the roof tiles.

The sides of this neat stack revealed the layers in cross-section, as sedimentation following its systematic collapsing. It was as if all air, all living space, had been evacuated from the building, returning it to a kind of orderly rubble.

Indeed, the building had been un-built but part of the entropic force in this case had been the question of value raised by the artists in the process of pulling down, relocating, cutting up and stacking a whole house. What was it worth? Did any value inhere in the material remnants, now detached from the home life, the land value, and the original design?

Cordeiro and Healy did the same thing to mobile homes in Melbourne and in Berlin. In Melbourne a caravan was taken apart piece by piece and each part was tagged and set out across the gallery floor, like an exploded view drawing of the components to be put back together. In Berlin the materials were neatly stacked directly onto palettes to be forward-freighted for exhibitions.

Their work is clearly indebted to process artists like Robert Smithson and Robert Morris – fragments taken from a landscape and framed within a gallery, piles of outlying junk introduced for their formal and aesthetic possibilities notwithstanding an occasional, basic aesthetic of squares and rectangles. But it also acknowledges and adapts IKEA methods and logistics, which have become all pervasive.

Indeed, IKEA has been flatpacking houses since 1996. And when a Swedish business magazine announced in 2004 that IKEA mogul Ingvar Kamprad was arguably richer than Bill Gates it reminded everyone that real space still mattered. As much as the miniaturization of electronics in computers had created a simulacrum of the world, flatpacking the computer desk and chair might have been an equally profitable innovation.

IKEA’s was a profound innovation too, since we wake from all our dreams in a bed, embodied, occupying space; analogue beings, subject to physical forces. (Cordeiro and Healy make the same point comically by flat-packing Doctor Who’s Tardis for ‘same day delivery’; despite the aspiration to time travel, we are still limited to corporeal transit.)

They say Isaac Newton discovered gravity reading a book under a tree after an apple fell on his head. IKEA engineer Gillis Lundgren discovered flat-packing while trying to fit a table into his car boot; he took the legs off, stowed them flat, and put them on again at home. All flat-packed IKEA furniture since is a curious form of measuring space since it shows us the value of things when occupying the least amount of space (flattening or collapsing things in production, storage, and transport reduces the cost). And thus one of the world’s most valuable enterprises is a curious testament – or simple accession – to gravity, which is also its connection to contemporary sculpture.

IKEA undoes furniture, exposing (and simplifying) the construction, just as ‘process art’ in the 70s undid traditional and modern sculpture. Typically, the use of art media defied gravity – elegant marble arms carved in space, steel beams cantilevered overhead, even paint thickened so as not to run. But gravity finally had its way with scattered debris (Robert Morris), molten lead (Richard Serra), and dripping paint (Morris Louis). Art materials were unbound.

But while process artists simply refused to finish making things according to traditional methods and expectations, not venturing past a certain point in their transformation of material, exposing the construction process and avoiding representation, Sean Cordeiro and Claire Healy literally undo, unbuild, disassemble.

Installation, 2005 enitre found objects within artist residency in Tokyo

They unwind screws, extract nails, separate tongue and groove flooring and interleaved tiles and timber. Industrial or manufacturing processes are set in reverse by hand (indeed, things are ‘hand-unmade’) and their significant labors not only hasten but neaten the ineluctable, tidal pull of the deterioration of all things, just as IKEA does in dismantling and neatly packing the unmade furniture.

Cordeiro and Healy go further in a series of works in which IKEA furniture is not only left unbuilt but further cut, routed, and eventually pulverized, that is, returned to particles.

Ashes to Ashes, 2008 pulverised Lack coffee tables in oak and glass vitrines Photographer- Uwe Walter

Unlike their antecedents, they do not merely subject their work to entropic forces but are active, commissioned agents, facilitating the final days of found materials; a kind of assisted obsolescence, with a few kind words and a fond remembrance at the graveside of the junk and leftovers they find around them.

They assemble and disassemble the stuff of the world that no-one owns or really wants, the contents of studios in Berlin and Tokyo, their own possessions in storage in Sydney; things not taken but not quite thrown away either. 175,000 outmoded, unwatched VHS tapes, literally a lifetime of video, stacked into a black monolith; a tomb, a headstone, a memorial.

A light prop-aircraft, arch-symbol of flight and exploratory transport: on the one hand arrested, confined and suspended mid-air within building scaffolding; and on the other, cut up, parceled, addressed and jet-air-mailed to its destination.

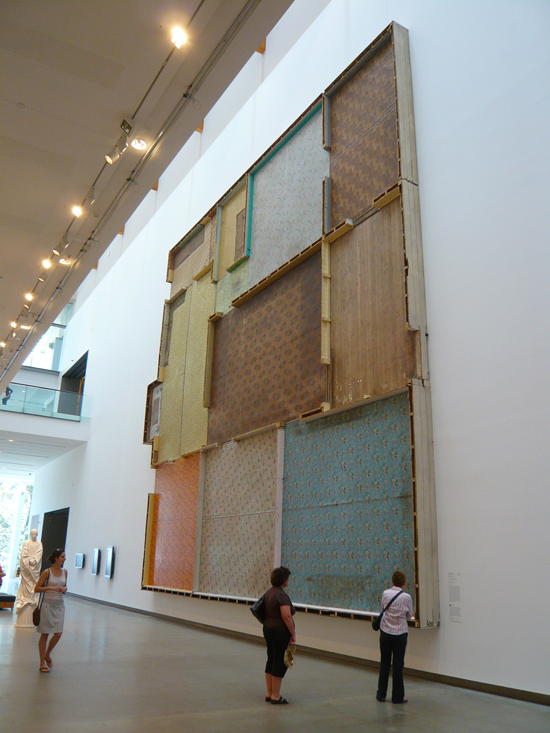

Obsolescence takes a little longer in the country where, as they say, the ‘past [has] not [been] put out of sight’, and things are left to rust and decay in full view. The entire floor of one abandoned farmhouse cut in cross-section was hung like a painting on the walls of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, a hard edge abstraction of passing fashions in linoleum and floorplans.

Working on an abandoned house in rural Australia (or an old kitchen cabinet) Cordeiro and Healy do not take it to bits but fill the empty, negative spaces with bright orange blocks of colour (either warning signs or bold affirmations).

Cordeiro and Healy describe the recto and verso of their interest in the occupation of space ‘stacking’ on the one hand, ‘unloading’ on the other. These alternate methods are like a breath inhaled and then exhaled, so that their collected works seems to heave up and down – air sucked out, space put back or filled.

A collection of second-hand world atlases are cutdown and perfectly fitted within IKEA standardized, unitary book-shelving. A dinosaur fossil is literally measured by the assortment of IKEA furniture that fills its hollow. A real Oak tree is cut up and neatly contained within IKEA oak veneer shelving.

In each case, assembled IKEA furniture becomes a new universal measure of the space occupied by the things they find; measuring the old by the new in a direct contiguous comparison, in a strange tribute a new era of space efficiency.

Curiously, in more recent works, IKEA furniture meets Lego (a new passion for Cordeiro and Healy) in a battle of the unitary assemblage systems; Lego – in the form of a snake or lion – spreading like a shape-shifting virus, partially enveloping a coffee table or hallway shelf.

These new space wars reflect Cordeiro and Healy’s abiding, shifting interests in the increasing systematization of space but also the larger paradigm shift from a static solid world to a portable, collapsible, mutable, stowable, temporary version.